Ferrari 365 Series: The Complete History (1966-1976)

The Ferrari 365 series represents the final chapter of Ferrari’s hand-built era. From 1966 to 1976, every curve was crafted by artisans in Maranello. Each V12 engine was assembled with precision that modern mass production could never replicate.

Nine distinct models defined this transformative decade in automotive history. From the ultra-rare California spider to the iconic Daytona berlinetta, these hand-built Ferraris remain highly sought by collectors who value provenance, authenticity, and the passion embedded in every panel.

Today, the 365Ferrari registry will document all of these remarkable machines, preserving their stories for future generations of enthusiasts.

Join the Community

Verified documentation. Trusted provenance. Shared knowledge.

The End of an Era: Why Ferrari 365 Models Matter

The 1960s and 1970s marked a pivotal transition in automotive manufacturing. While competitors embraced mass production, Ferrari’s 365 series maintained traditional hand-built craftsmanship that would soon disappear.

Hand-Built Excellence

Each car rolled out of Maranello with artisan-built bodywork, hand-assembled engines, and attention to detail that prioritized quality over volume. As one collector observed, these cars embodied “the heart and soul of those older cars…everything was hand-built. They’re all swoopy and sexy and something you could look at as a piece of art.”

Cultural Impact

The cultural significance extended beyond Maranello. Ferrari 365 models appeared alongside Hollywood icons, graced prestigious automotive events, and established the brand’s reputation for combining performance with elegance. Unlike later mass-produced models following Fiat’s acquisition, the 365 series retained the boutique character that made Ferrari legendary.

Why Documentation Matters

Today, documentation and provenance matter more than ever. Verified ownership histories, original specifications, and restoration records can increase a 365’s value by 10% or more at sale.

This is why the 365Ferrari registry exists—to document, verify, and preserve the history of every Ferrari 365 we can locate.

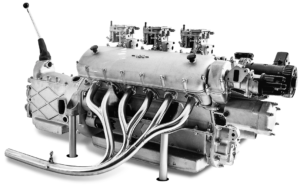

The Colombo V12: Heart of the Ferrari 365

Most Ferrari 365 models share a common foundation: the legendary Colombo V12 engine. Designed by Gioacchino Colombo, this 4.4-liter (4,390cc) 60-degree V12 produced between 320 and 352 horsepower depending on configuration. The engine appeared in two main variants across the 365 series: 2-cam versions in earlier models and more powerful 4-cam versions in performance-focused cars like the GTB/4 Daytona.

Colombo V12 Specifications:

- Displacement: 4,390cc (4.4L)

- Configuration: 60° V12

- Power: 320-352 hp (varies by model)

- Compression: 8.8:1 to 9.3:1

- Fuel system: Weber carburetors (6x 40mm)

What made the Colombo V12 special wasn’t just its technical specifications; it was the hand-assembly process. Each engine was built by skilled technicians who understood that precision mattered more than production speed. This naturally-aspirated V12, fed by six Weber carburetors, delivered power with a linear, predictable character that modern turbocharged engines struggle to replicate. The sound alone—a crescendo from idle to redline—remains one of the most distinctive in automotive history. This engine’s influence continues in modern Ferrari V12s like the 812 Superfast and Purosangue.

The shared Colombo architecture across most 365 models means parts compatibility is better than expected. Transmissions, braking systems, suspension components, and many trim elements interchange between models, making ownership and restoration more feasible than for truly unique Ferrari variants.

The Hand-Built Ferrari Era

Ferrari’s final decade of true hand-crafted production—where engineering, individuality, and provenance came before mass manufacturing.

Complete Ferrari 365 Model Lineup: All 9 Variants

The Ferrari 365 series produced nine distinct models over its ten-year production run. Each served a different purpose-from practical grand tourers to exotic competition machines-but all shared the DNA of hand-built Italian craftsmanship. Production numbers varied dramatically, from just 14 California spiders to over 1,200 Daytona coupes, making certain models significantly rarer than others.

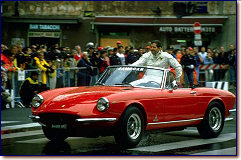

1. Ferrari 365 California (1966-1967)

The Ferrari 365 California stands as the rarest 365 variant with only 14 examples produced worldwide. This elegant open-top spider featured Pininfarina bodywork and represented the final “California” nameplate before its modern revival decades later. As successor to the legendary 250 California, the 365 California continued Ferrari’s tradition of elegant open-top gran turismos. The 320-horsepower Colombo V12 provided effortless performance in what was essentially a hand-built exotic for discerning collectors. Today, authenticated examples command premium pricing when they rarely appear at auction.

2. Ferrari 365 GT 2+2 (1967-1971)

With approximately 800 examples produced, the Ferrari 365 GT 2+2 was the most common 365 model. This practical grand tourer offered genuine 2+2 seating, making Ferrari ownership accessible to families who needed space alongside V12 performance. The Pininfarina coupe design balanced elegance with practicality. Available with either a 5-speed manual or 3-speed automatic transmission producing 320 horsepower, it remains an attainable entry point to 365 ownership today while delivering authentic Ferrari character.

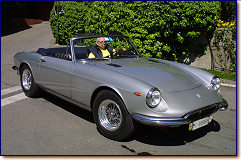

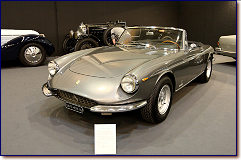

3. Ferrari 365 GTC (1968-1970)

The Ferrari 365 GTC produced 168 examples of refined 2-seater gran turismo elegance. More understated than the Daytona, the GTC offered balanced performance and luxury in a timeless Pininfarina design. Its 320-horsepower V12 provided effortless high-speed touring capability wrapped in elegant, understated coachwork. Today, the GTC is recognized as an underappreciated gem gaining significant collector interest as enthusiasts discover its refined character.

4. Ferrari 365 GTS (1968-1969)

Only 20 examples of the Ferrari 365 GTS spider were produced, making it one of the rarest 365 variants after the California. This open-top version of the GTC featured a removable hardtop and elegant spider proportions that captured the essence of 1960s Ferrari design. The combination of extreme rarity, elegant Pininfarina bodywork, and 320-horsepower V12 performance ensures these cars rarely reach the market. When authenticated examples appear, they command significant premiums from serious collectors.

5. Ferrari 365 GTB/4 “Daytona” (1968-1973)

The Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Daytona is the most iconic 365 model, with 1,284 coupes produced. Its unofficial “Daytona” nickname came from Ferrari’s 1-2-3 finish at the 1967 24 Hours of Daytona. This aggressive berlinetta featured a 4-cam V12 producing 352 horsepower—the most powerful 365—and achieved a 174 mph top speed that made it the world’s fastest production car at launch. The Daytona represented Ferrari’s answer to Lamborghini’s mid-engine Miura, proving front-engine configurations could still dominate. Its angular Pininfarina design, combined with legitimate racing heritage through Competizione versions, established the GTB/4 as a blue-chip Ferrari investment. Cultural appearances in Miami Vice cemented its legendary status.

6. Ferrari 365 GTS/4 (1969-1974)

The Ferrari 365 GTS/4 offered open-top excitement with only 121 spiders produced. Featuring a removable Targa-style top and the same 352-horsepower 4-cam V12 as the coupe, the GTS/4 provided wind-in-hair V12 performance with iconic spider proportions. Rarity makes it significantly more valuable than the GTB/4 coupe, with pristine examples commanding seven-figure prices at auction today.

7. Ferrari 365 GTC/4 (1971-1972)

The Ferrari 365 GTC/4 produced 505 examples with unique 2+2 shooting-brake influenced styling. Its distinctive rear design divided opinions when new but has gained significant appreciation for practicality and advanced features including optional air conditioning and power steering. The 4-cam V12 produced 340 horsepower, making it both fast and livable for daily use—the most practical 365 for enthusiasts who drive regularly.

8. Ferrari 365 GT4 2+2 (1972-1976)

The Ferrari 365 GT4 2+2 produced 525 examples as the final 365 series 2+2. Sharp, angular Bertone-influenced design marked the transition to 1970s automotive aesthetics. The 4-cam V12 produced 340 horsepower while maintaining practical 2+2 seating. As the last 365-designated 2+2, it represents an affordable entry point to 365 ownership today while delivering genuine Ferrari V12 performance.

9. Ferrari 365 GT4 BB “Berlinetta Boxer” (1973-1976)

The Ferrari 365 GT4 BB marked Ferrari’s revolutionary shift to mid-engine architecture with 387 examples produced. Unlike other 365 models, the BB used a flat-12 “boxer” engine rather than the traditional Colombo V12. This 380-horsepower wedge-shaped berlinetta was Ferrari’s response to the Lamborghini Countach and bridged the gap to the 512 BB era. Some purists don’t consider it a “true” 365 due to the different engine architecture, but it represents an important transition in Ferrari’s evolution.

Ferrari 365 Production Timeline (1966-1976)

The Ferrari 365 story unfolded over a transformative decade. Production began in 1966 with the rare California spider, followed by the practical GT 2+2 in 1967. The watershed year of 1968 introduced the iconic GTB/4 Daytona alongside the refined GTC. By 1969, the GTS/4 spider added open-top V12 excitement. The early 1970s brought the unique GTC/4 in 1971, the updated GT4 2+2 in 1972, and the revolutionary mid-engine GT4 BB in 1973. Production concluded in 1976 as Ferrari transitioned to the 400 and 512 series.

Approximately 3,800 Ferrari 365s were produced across all nine models, making them rare but not unobtainable. Multiple models were often sold simultaneously, showing Ferrari’s range from practical grand tourers to exotic performance machines. This period coincided with significant automotive challenges, including the 1970s oil crisis and emerging emissions regulations, making the 365 series one of the last expressions of unrestricted V12 performance. The transition from hand-built production to Fiat-influenced mass production marked the end of an era in Ferrari’s storied history.

Why Ferrari 365 Documentation Matters

Provenance transforms a Ferrari 365 from a classic car into documented automotive history. Verified cars sell for 20% premiums at auction, while undocumented examples raise questions about authenticity, maintenance and history. Ownership chain verification, original specifications, and restoration documentation are increasingly required for Concours d’Elegance events, prestigious auctions through houses like RM Sotheby’s, and platforms like Bring a Trailer where documentation directly impacts final sale prices.

Pre-purchase verification protects buyers from costly mistakes. VIN and chassis number authentication, matching numbers confirmation for engine and transmission, and service history review can reveal problems before purchase. The 365Ferrari registry provides documentation and verification services for 365Ferrari members, ensuring every entry meets rigorous standards.

Historical preservation benefits the entire community. With only 3,800 total 365s produced, each car represents irreplaceable automotive history. Collective knowledge about production quirks, model-specific issues, and ownership histories preserved in registries benefits all owners and enriches our understanding of this remarkable era.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Ferrari 365 Series

How many Ferrari 365s were produced in total?

Approximately 3,800 Ferrari 365s were produced across all 9 models from 1966-1976. The 365 GT 2+2 was the most common, with around 800 units, while the 365 California was the rarest, with only 14 examples worldwide.

What’s the most valuable Ferrari 365 model?

The Ferrari 365 GTB/4 “Daytona” commands the highest values, with pristine examples exceeding $750,000-$1M+. The ultra-rare 365 GTS/4 spider (121 produced) often surpasses the coupe at auction. The 365 California (14 produced) is also extremely valuable when examples appear at major auctions.

Do all Ferrari 365 models use the same engine?

Most 365 models use variants of the Colombo V12 (4.4L, either 2-cam or 4-cam configuration). The exception is the 365 GT4 BB “Berlinetta Boxer,” which uses a mid-mounted flat-12 engine instead of the traditional Colombo V12 architecture.

Are Ferrari 365 parts still available?

Yes, many parts remain available through specialist suppliers. Because the Colombo V12 was used across multiple Ferrari models and the 365 models share many components (transmission, brakes, suspension), sourcing parts is more feasible than for truly unique models. The 365Ferrari community also helps owners locate rare parts through the member marketplace.

How do I verify a Ferrari 365’s authenticity?

Verification requires checking the chassis number against Ferrari production records, verifying matching numbers (engine, transmission), examining original factory specifications, and reviewing ownership history. The 365Ferrari registry provides documentation and verification services for members. Pre-purchase inspections by qualified Ferrari specialists are always recommended.

What should I look for when buying a Ferrari 365?

Key considerations include documented ownership history, matching numbers (chassis, engine, transmission), restoration quality and documentation, comprehensive service records, chassis condition (rust, accident damage), originality versus modifications, and current market value for the specific model and condition. Join 365Ferrari to access buyer’s guides and connect with experienced owners before making your purchase.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

The 365Ferrari Registry: Preserving Automotive History

The Ferrari 365 series represents the pinnacle of Ferrari’s hand-built era. Nine distinct models, each with a unique character and purpose, defined a transformative decade in automotive history. Documentation and provenance are increasingly important as these cars appreciate and change hands among collectors worldwide.

The 365Ferrari registry preserves this automotive history for current owners, future collectors, and enthusiasts. Our comprehensive database currently documents over 87 Ferrari 365s across all nine models, with each entry personally verified by our founder. We maintain serial numbers, production specifications, ownership histories, restoration records, and provenance chains that increase value and ensure authenticity.Whether you own a Ferrari 365 or simply admire these hand-built masterpieces, you belong here. Register your Ferrari 365 to preserve its history, increase its value, and connect with a global community of owners and enthusiasts who share your passion for Ferrari’s hand-built era. Join 365Ferrari membership to access the complete database, connect with owners worldwide, and contribute to preserving automotive history for future generations.